By Zachary Fitzgerald

zfitzgerald@daily-review.com

Ginesse Listi has spent over two decades working to put a name and face to hundreds of people whose remains have been found throughout Louisiana.

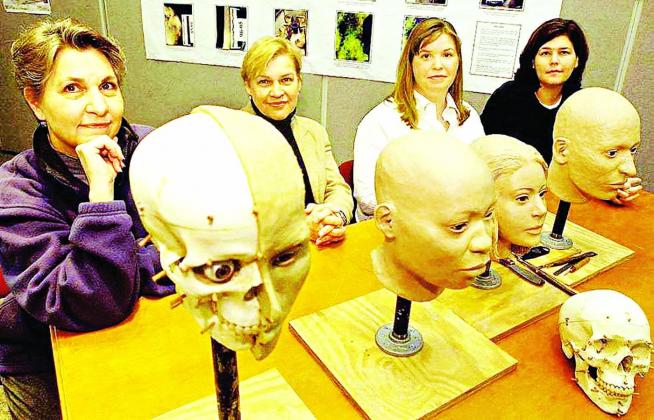

Listi, 45, who grew up in Morgan City, is director of LSU’s Forensic Anthropology and Computer Enhancement Services Laboratory, commonly known as the FACES lab. The mission of the lab is to identify unidentified human remains in Louisiana.

Louisiana has about 250 active missing persons cases and 150 active unidentified cases “that have grown cold over the years,” she said. The oldest case is from 1979.

Listi attended Morgan City High School for two years before leaving to attend Louisiana School for Math, Science and the Arts.

Mary Manhein, the former longtime director of the FACES lab, sparked Listi’s interest in forensic anthropology when Listi signed up for Manhein’s Anthropology 1001 course as a freshman at LSU.

Listi took over from Manhein as interim director of the lab in 2015 on Manhein’s retirement and then became permanent director in 2016.

The FACES lab’s role as the state’s repository for missing and unidentified people is “a huge part of what we do,” Listi said. An important part of a forensic anthropologist’s job is to use skeletal remains to figure out who the person was and what happened to him or her, Listi said.

In 2006, the state Legislature created the Louisiana Repository for Unidentified and Missing Persons Information Program and designated the FACES lab as that repository.

The lab receives state funding to provide those services.

Under state law, the lab is required to maintain a database of all of the missing and unidentified persons’ cases in the state.

The lab partners with law enforcement agencies and coroner’s offices to compile their information on missing and unidentified persons. FACES lab officials also input Louisiana data into the national database.

While taking Manhein’s introductory anthropology course as a college freshman, Listi found a segment on forensic anthropology extremely interesting.

Listi had planned to major in pre-med and work toward becoming a doctor.

“I wasn’t hooked immediately in terms of changing my career,” Listi said.

But Listi continued to take anthropology courses.

“I was really just fascinated with the skeleton and everything you could learn from it,” she said.

By her junior year at LSU, she decided she didn’t want to be a doctor because she didn’t like chemistry.

She was then accepted into the master’s degree program at LSU in forensic anthropology and started volunteering in the lab there.

The forensic anthropology lab at LSU was founded in 1980. Manhein began running the lab in 1987.

“It was Mary who actually turned a traditional forensic anthropology lab into the FACES lab,” Listi said.

Manhein started doing the clay facial approximations from skulls.

In the early 1990s, Manhein partnered with the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children to designate the LSU forensic anthropology lab as a “model age progression site,” Listi said.

This designation enabled LSU to offer training and receive equipment to do age progressions on missing people, and enhancing photos and taking still images from video, she said.

In 1993, “the FACES lab was born,” she said.

“We offered the forensic services, but then we started offering the computer enhancement services,” Listi said.

Listi began volunteering as a graduate student in the FACES lab in 1994.

“From that point forward, it just kind of snowballed,” Listi said.

Listi eventually became an assistant to Manhein. They worked on a grant research project to measure facial tissue thickness in children to have standards to create facial approximations from skeletal remains.

“That project turned into a full-time position (in the lab),” he said.

Listi then set her sights on earning a doctoral degree. Though Manhein achieved great success in her field without a Ph.D., both Listi and Manhein knew that the future of the field would require Listi to get another degree, Listi said.

So, in 1999, Listi started working on her doctoral degree at Tulane. Manhein and Listi kept in touch during that time.

When Listi finished her coursework at Tulane, a position became available in LSU’s FACES lab. Listi took the job and moved back to Baton Rouge in 2001. She finished her Ph.D. in 2008.

Listi and Manhein worked on many projects together. They assisted in putting displaced cemetery remains back in place after several hurricanes.

“Everything she worked on, I worked on,” Listi said.

Listi also teaches undergraduate and graduate level classes. Additionally, members of the lab do research on the bodies of people who have donated their bodies to science. That research can be applied to the cases anthropologists work, Listi said.

The methods that forensic anthropologists use to try to identify the age of a person based on their remains are most effective for young people and “middle to early old age,” she said.

“A lot of our standards end or they become less reliable the older you get,” Listi said.

Methods to determine age aren’t as useful for people over 60 years old. A few years ago, Listi did a research project where she examined degeneration in the skeletons in hip and knee joints of people who had donated their bodies to science. Studying those known collections of skeletons then gives forensic anthropologists a way to narrow the age range of unidentified older people.

Dealing with death all the time is sad and challenging, particularly seeing the cruel ways that humans sometimes treat one another, Listi said.

“Being able to work with students and being able to teach helps to mitigate some of that (sadness) because they’re usually more optimistic,” she said.

Listi’s parents, Gerald and Frances Listi, still live in Morgan City. Frances Listi worked for the St. Mary Parish School Board for many years, while Gerald Listi recently retired from M C Bank.