Jim Bradshaw

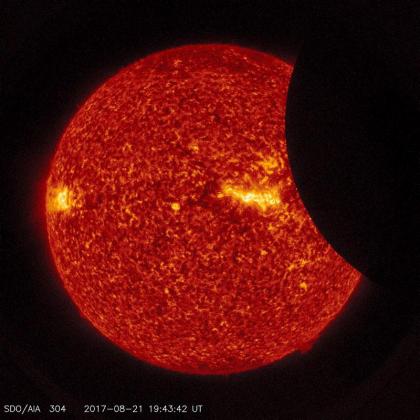

The great eclipse that stirred so much anticipation across the middle of the United States was pretty much a dud at my house. I’m not sure I would have noticed anything if it hadn’t been for the big build-up. The sky dimmed only to something akin to a slightly overcast day, which seems to be what’s happened during most solar eclipses viewed from south Louisiana.

For example, the St. Martinville Messenger recorded on June 2, 1900, that “all the people of the town were out looking at the eclipse, but they were all disappointed.”

According to the Messenger, there was a much more satisfying eclipse on July 29, 1878, when it became “so dark that it was necessary to light the lamps in the stores and houses,” but the disappointing 1900 eclipse, like this one in 2017, “simply looked like a cloudy day.”

Nonetheless, the Opelousas Courier warned before that event that it could cause strange things to happen. People could become “nervous and excited.” Children would “cling to their mothers in fright.” Chickens would go to roost and cows come in from the pasture.

“While the darkness lasts,” the warning continued, “there is a brooding dullness among all living things except dogs and wolves. These set up a snappish yelping quite different from the ordinary bark or night howl.”

The New Orleans Item said the 1900 event would be the first visible in the city “since civilized man set his foot here,” but that wasn’t quite correct — although I guess that could depend not only on the date of the eclipse but on when men became “civilized” in the Crescent City.

Baton Rouge newspapers had urged their supposedly civilized readers to have smoked glasses ready to view an eclipse on October 18, 1865, even though it would not be “large enough totally to obscure the sun.” In the view from Louisiana, the paper said, two-thirds of the sun would be covered, and it would become dark enough that “should the atmosphere be serene, several planets and fixed stars will be visible.”

The St. Landry Democrat carried a long article about the eclipse of May 6, 1883, even though it could be seen only over “a vast extent of watery waste” in the Pacific. Two tiny islands, Caroline Island and Flint Island, were apparently the only dry spots available for watching it.

“Thousands of miles of ocean must be traversed, and all manner of privations and hardships must be endured in order to behold the awe-inspiring spectacle,” according to the newspaper. “But never yet in the history of the human race have any difficulties in the way prevented zealous men of science from attempting to fathom the mysteries that enshroud our celestial neighbors.”

The Morgan City Daily Review said the one on June 8, 1918, would be visible in south Louisiana only as a partial eclipse; the center of the shadow would be 150 miles northeast of New Orleans, and “we will see none of the really interesting phenomena.” But, even so, in the Review’s estimation, the eclipse was “the most notable astronomical event … predicted for the present year, and the people of the United States are sincerely fortunate in having the spectacle staged at home for them.”

There have been a handful of solar eclipses that tracked across the Gulf of Mexico — including in 1908, 1919. 1923, and 1970 — but probably our most exceptional recent view came on May 30, 1984, when, according to the New York Times, “From Louisiana to North Carolina, people … were afforded a rare glimpse of a nearly total solar eclipse that turned noontime into an eerie twilight and briefly framed the black shadow of the Moon in a spectacular necklace of light.”

The deepest shadow traced an arc that passed “just north of New Orleans and Montgomery, Ala., (and) directly over Atlanta,” where, according to the Times, “the temperature dropped six degrees, flowers closed their petals, dogs howled, pigeons tucked their heads under their wings as if to sleep, and the whole city was bathed in a kind of diffused light, not unlike that accompanying the approach of a severe storm.”

That wasn’t quite the spectacle we got with this latest eclipse, but they’ll always be another one. Circle the dates: The next best chances for a good view from Louisiana appear to be in October 2023 and April 2024. Keep those smoked glasses handy and stay ready to fend off snappish wolves.

A collection of Jim Bradshaw’s columns, Cajuns and Other Characters, is now available from Pelican Publishing. You can contact him at jimbradshaw4321@gmail.com or P.O. Box 1121, Washington LA 70589.